The fixed-for-fixed rule creates numerous accounting distortions and extreme incoherence. That rule originated about 20 years ago from a similar rule under US GAAP. Unlike other rules, this rule changed the distinction in the accounting constitution between equity and liabilities and created an independent definition of equity. The high expectations from the IASB’s promise in 2018 to fix the distortions led to a major disappointment, since the new proposal only perpetuates the problem, and it does so without even amending the Conceptual Framework. Furthermore, even the rule-based US GAAP provides some exceptions where the substance of the instrument is equity. Therefore, a fundamental solution is required, replacing the rule with a principle for distinguishing between equity and liabilities, in line with principle-based standard setting. In addition to the lack of an obligation to transfer economic resources, the decisive criterion for equity classification should be substantial exposure to the risks and rewards of ownership of the shares.

In November 2023, the IASB published an Exposure Draft – Financial Instruments with Characteristics of Equity, proposing amendments to IAS 32. Among other things, the ED underscores the existing distortion in classifying an instrument as a financial liability based on the fixed-for-fixed condition. The ED follows a Discussion Paper published in 2018, which stated that: “IAS 32 does not provide a clear rationale for the requirements in relation to obligations settled by delivering an entity’s own equity instruments… The lack of a clear and consistent rationale in IAS 32 and in the Conceptual Framework, makes it difficult for the Board to develop consistent classification requirements across IFRS Standards”. When reading the very strong statement in 2018, I was hoping for a solid principle-based standard setting. However, in 2023, after patiently waiting five years, I was extremely disappointed by the proposals in the current ED.

From a historic perspective, the fixed-for-fixed condition originated about 20 years ago from a similar rule under US GAAP. The purpose behind the fixed-for-fixed condition was to classify an instrument as equity only where the holder has a residual interest in the reporting entity’s assets after deducting all its liabilities. However, the phrasing of the condition as a rule, rather than a principle, creates various problems and accounting distortions.

In a typical example, an investor invests CU10 million in a Company whose current share price is CU10. Assuming an annual interest rate of 5%, after one year the Company has an obligation to issue a million shares in scenario A or, in scenario B, an obligation to issue a variable number of its own shares calculated by dividing 10.5 million by the share price on settlement. In effect, the holder in scenario B has the right to receive as many shares as required to provide it with a value of CU10.5 million on settlement. Hence, the Company uses its own shares as currency to settle its obligation.

In that basic example, the same conclusion can be reached by both the rule and the principle. In scenario A, the holder is exposed to changes in the share price of the Company during the period between issuing the instrument and settling it, just like an outright shareholder is. In contrast, in scenario B the holder is unaffected by changes in the share price until the date of settlement. It is only from that date onwards that the holder will be exposed to the risks and rewards of ownership of the shares. From the holder’s perspective, until that date it effectively holds a debt instrument, generating a fixed return of 5%. Consequently, the instrument is classified as equity in scenario A, while in scenario B it is classified as a financial liability.

A common example in recent years that illustrates the principle of classifying a variable number of shares as a liability rather than equity is the issuance of SAFE (Simple Agreement for Future Equity) in startup companies. The main motivation behind this instrument is the deferral of determining the share value, which allows the issuing companies and investors to avoid a down round at the investment stage. Classifying these fundraisings as liabilities rather than equity reflects the nature of the issuance, which is borrowing until the value is determined in the future.

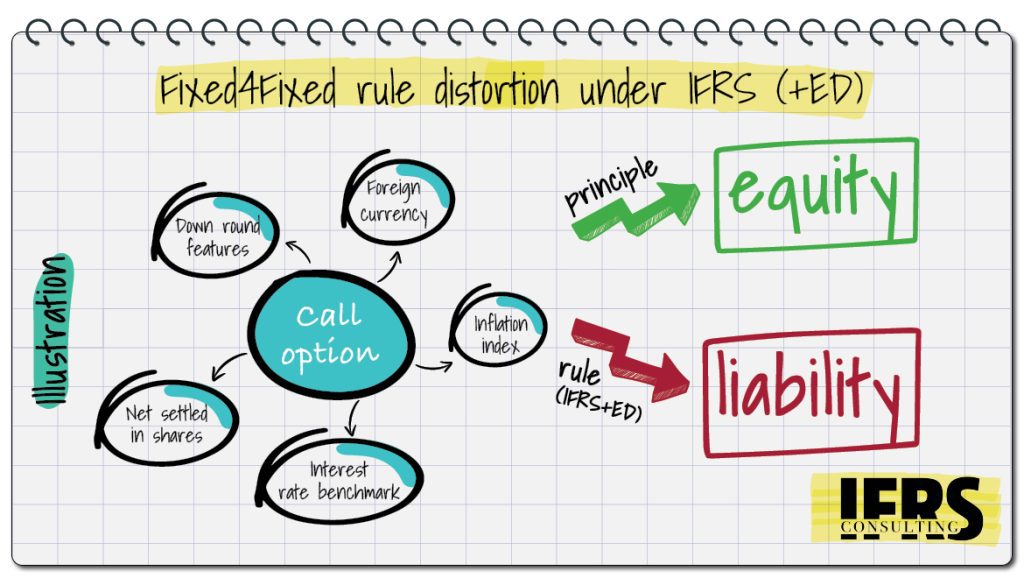

The problem is that most instruments fall in the range between those two clear points, and due to the strictly worded fixed-for-fixed rule, they are inevitably classified as financial liabilities. While the example above does not deal with a derivative, the same logic similarly applies to a derivative, where to be classified as equity both its legs are required to be fixed – the number of shares to be delivered and the amount of cash to be received. Hence, the ED explicitly proposes, for example, that where the exercise price of a call option to buy shares of the reporting entity varies with a foreign currency, inflation index or interest rate benchmark, the option shall be classified as a financial liability. Although in such cases the holder is exposed to those variables in addition to its exposure to the risks and rewards of ownership of the shares, the strict fixed-for-fixed rule prevents the option from being classified according to its substance as equity.

Call option – a “double attack”

To illustrate the distortion in practice, it should be noted that since adopting IFRS in 2008, virtually all listed entities in Israel no longer issue inflation-linked options, a practice that was common before the adoption of IFRS. A situation where an accounting rule leads to such a significant business change demonstrates the “quality” of that rule.

The distortion is best illustrated with a call option over shares, to be net settled in shares, where the number of shares to be delivered is based on the share price on the date of settlement. Under the proposed ED, since the instrument will be settled by delivering a variable number of shares, the option is classified as a financial liability. Nevertheless, in a principle-based world, the classification of an instrument should not be determined solely by the form of the settlement, but rather by its substance. Therefore, where the investor’s risks and rewards are identical, the same classification should be applied regardless of the form of settlement, whether net or gross. Thus, as long as the investor is exposed to changes in the issuer’s share price until settlement, both forms of settlement should have been classified as equity. This substance-over-form approach will also solve the existing inconsistency between IAS 32 and IFRS 2 when classifying such net-settled options.

Moreover, the classification of instruments such as a call option to be net settled in shares or a call option whose exercise price is linked to a foreign currency, has a direct impact not only on the statement of financial position, but also on the statement of comprehensive income. Since those options are classified as financial liabilities, they are generally measured at fair value, with changes in fair value recognized in profit or loss. Accordingly, reflecting these fair value changes in profit or loss is counterintuitive, since a gain is recognized when the fair value of the issuer’s shares decreases, whereas when their fair value increases – a loss is recognized. In other words, the more successful the issuer’s business becomes, the greater the damage inflicted on its net profit and retained earnings, so that instead of recognizing the underlying instrument as equity in the first place, the classification as a liability damages the equity the issuer had prior to that issuance – a “double attack”, to those familiar with chess tactics…

As stated above, the origin of the fixed-for-fixed condition is US GAAP. However, even the rule-based US GAAP provides some exceptions where the substance of the instrument is equity, e.g., in cases of down round features or where adjustments are made based on changes in the reporting entity’s share price. Regrettably, the instruments in those cases would be classified as financial liabilities under the IASB’s proposed ED. In fact, the example above where a call option is net settled in shares is a typical IFRS vs. US GAAP difference, which leads to a significant disadvantage for European companies applying IFRS, that are listed on a U.S. stock exchange.

The Conceptual Framework: the tail that wags the dog

Furthermore, the classification of an obligation to deliver a variable number of the reporting entity’s own shares as a liability is inconsistent with all versions of the IFRS Conceptual Framework – the original version published in 1989, the version issued in 2010 and even the revised version issued in 2018. All those versions define a liability based on a present obligation to transfer economic resources, rather than the reporting entity’s own shares. Thus, the discussion should start with the lack of an appropriate accounting infrastructure of principles, which leads to adopting a rule that creates numerous accounting distortions.

Indeed, the Exposure Draft of the revised Conceptual Framework published in 2015 proposed that an obligation of a reporting entity to transfer its own shares will never be classified as a liability, even for an obligation to deliver a variable number of shares with a fixed total value. However, this principle was removed from the final version, because, as stated in the IASB’s Summary of Tentative Decisions, it was: “inconsistent with existing IFRS requirements”. The tail is wagging the dog.

A proposed solution

Although the fixed-for-fixed condition was originally a rule, I believe the solution should be found in adopting a principle-based approach. Thus, to be classified as equity, two criteria shall be met:

- The reporting entity has no obligation to transfer economic resources, and

- The holder is substantially exposed to the risks and rewards of ownership of the shares (or other residual interests).

It should be noted that equity is defined in the Conceptual Framework as the residual interest in the assets of the reporting entity after deducting all its liabilities. Therefore, the equity classification mentioned above should be achieved by changing the definition of a liability. Accordingly, for the definition of a liability to be met, one of the following criteria shall be satisfied:

- The reporting entity has a present obligation to transfer economic resources, or

- There is no such obligation, but the holder of the instrument is not substantially exposed to the risks and rewards of ownership of the shares (or other residual interests).

To conclude, it is much easier for standard setters to set narrowly defined rules, than to determine the overall principle. However, when trying to solve specific problems without taking account of the big picture, the solution could lead to unintended consequences, creating even bigger distortions. It is extremely important to have an appropriate process of standard setting, where a profound constitutional change is first made to the Conceptual Framework, and only then it is adopted as guidance in the financial reporting standards. Indeed, under the accounting hierarchy an IFRS requirement overrides the concepts in the Conceptual Framework. Nevertheless, an intended exploitation of that hierarchy is particularly problematic. Thus, in principle, the requirements in IFRSs should be developed based on consistent concepts described in the Conceptual Framework, just like the laws of a country should be enacted in line with the principles specified in its constitution.

(*) Written by Shlomi Shuv