A share-based derivative with settlement alternatives at the discretion of the issuer is currently classified under IAS 32 as a financial liability solely to prevent manipulations, resulting in an accounting distortion. The use of anti-abuse provisions in accounting standards is reasonable as long as the benefits of preventing manipulations outweigh the disadvantages that could undermine neutrality and create new accounting distortions. The major anti-abuse provisions in IFRS can be divided into three groups according to their degree of legitimacy: provisions that are clearly legitimate (green group), provisions whose justification is questionable (yellow group) and provisions leading to accounting distortions (red group).

One of the guiding accounting principles in classifying a financial instrument as a liability or equity lies in who has the discretion to redeem the instrument. Where the discretion lies with the issuer, the instrument is classified as equity, whereas if it lies with the holder the instrument is classified as a financial liability. Nevertheless, for a share-based derivative whose settlement method is at the discretion of the issuer, it is enough that one of the settlement alternatives will lead to a liability classification, for the derivative to be classified under IAS 32 as a financial liability. To illustrate, assume that a company whose functional currency is USD issues a call option for one share, with a strike price of $100 and issuer discretion regarding the settlement method. On settlement, the share price increases to $120, the option is in the money and the holder decides to exercise and benefit from the share price increase. Upon receiving the exercise notice, the issuer may choose between a payment of $20 cash (net settlement) and receiving $100 cash along with the issuance of one share (gross settlement). In this case, despite the fact that the gross settlement alternative is generally classified as equity since it meets the fixed-for-fixed condition, IAS 32 requires the entire instrument to be classified as a financial liability, because the cash settlement alternative would constitute a liability.

The rationale provided by the IASB for that requirement is an anti-abuse concern, its goal being preventing entities from circumventing requirements regarding classification of financial liabilities (cash settlement) by adding an equity option at the discretion of the issuer, that enables the instrument to be settled by delivery of a fixed number of shares for a fixed amount of cash.

To grasp the magnitude of the distortion, it should be noted that had it been a non-derivative instrument, giving the issuer the choice between payment of $120 cash and issuance of one share, it would be classified as equity, since the issuer has an unconditional contractual right to avoid delivering cash by issuing one share. Notably, classification of a derivative as a financial liability has a dual impact – not only on its presentation as a liability, but also on its measurement, which can lead to a distortion in measuring the results of the issuer. That is because as the issuer’s performance improves and its share price rises, the fair value of the derivative will rise accordingly, leading to a counterintuitive increase in the liability and a corresponding recognition of a loss, and vice versa. It should be mentioned that under US GAAP there is no similar anti-abuse provision, so an issuer’s settlement alternative that includes an equity option, leads to equity classification of the entire instrument, since the issuer has an unconditional contractual right to specifically choose the “equity” settlement.

The scale between legitimate and creation of a distortion

It is important to emphasize that the use of anti-abuse provisions in accounting standards is sometimes justified. There is logic in including such provisions to limit manipulations rather than leaving the task solely to auditors and the relevant enforcement institutions, such as securities regulation authorities. However, care must be taken when the anti-abuse provisions undermine the neutrality of the accounting treatment itself. The key question is whether the benefits of preventing manipulation compensate for the disadvantages which could reach as far as creating new accounting distortions.

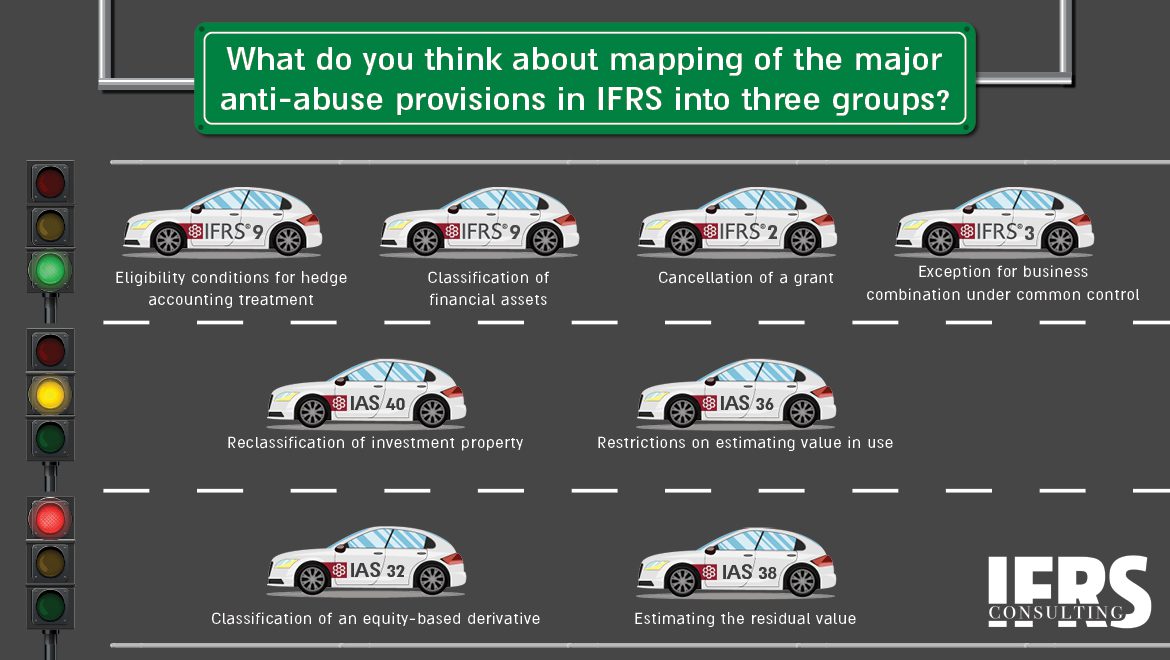

The major anti-abuse provisions in IFRS can be divided into three main groups: ranging from those provisions for which the price of preventing manipulations is not too high (green group), through provisions whose justification is questionable (yellow group), to provisions leading to significant accounting distortions (red group), such as the case of share-based derivatives. It is important to note that the green group includes anti-abuse provisions in relatively new IFRSs, whereas the other two groups relate to older IFRSs.

Distinguishing between adherence to economic substance versus anti-abuse provisions

The table below includes a mapping of the major anti-abuse provisions in IFRS into each of the above three groups. In this context, it is important to distinguish between anti-abuse provisions and instances in which the accounting standard places specific emphasis on economic substance to create deterrence, as should have been the case in any event under the principles in the Conceptual Framework. For example, when the acquirer in a business combination is required to make contingent payments, IFRS 3 distinguishes between future remuneration for the services of the seller and the cost of the acquiree, using several indicators. However, if payments are automatically forfeited when employment terminates, the contingent payments would always be accounted for as future remuneration, even if all the other indicators suggest otherwise. Similarly, IFRS 15 and IFRS 10 include a requirement to combine two or more contracts and account for them as a single contract, with an impact on the timing of revenue recognition and on losing/obtaining control, respectively.

The green group includes a requirement to designate financial assets on initial recognition into a certain measurement category, as well as restrictions on subsequent transfers among the various measurement categories in accordance with IFRS 9. Considering the existing accounting model, these requirements are legitimate since there is a justified concern that entities will retrospectively designate or reclassify financial assets into a favorable measurement category, after observing the actual results. Similarly, IFRS 9 requires formal designation and documentation of a hedging relationship at the inception of the hedge, to prevent a retrospective decision regarding whether to apply hedge accounting after the results are already known.

Another case that can be attributed to the green group is the requirement in IFRS 2 to accelerate the expense recognition in the event of cancellation of a grant of equity instruments, due to concerns that entities will avoid continuing to recognize salary expenses for out-of-the money employee stock options (which are already not significant from the employee’s perspective). In that case, the justification for the anti-abuse provision lies in the obvious distortion in the basic accounting model for recording expenses for equity-settled employee compensation – measurement at fair value at grant date rather than fair value over the service period. To be clear, the requirement to accelerate the expense is not desirable, as it can also be used conversely for earnings management by bringing forward losses in certain situations. Nevertheless, accelerating the expense seems unavoidable due to the fundamental flaw in the existing measurement model.

Moving to the other end of the scale, the red group can include the requirement in IAS 38 to assume a zero residual value for the purpose of amortizing intangible assets that have no active market or purchase commitment by a third party. Just like the cases above, the rationale of the IASB in this case also involves anti-abuse considerations. The stated purpose is to prevent entities from circumventing the requirement to amortize an intangible asset with a finite useful life by claiming that the residual value equals or exceeds its carrying amount. In fairness, it should be noted that this requirement is not unique to IFRS, as it also exists under US GAAP. It is important to understand that assuming a zero residual value could lead to an accounting distortion of over-recognizing amortization expense until disposal, with a gain recognized upon disposal. To illustrate the distortion, it is noted that an acquirer in a business combination, for example, is required to estimate the fair value of such an intangible asset. In this context, there is obviously a concern that allocating a zero amount to identified intangible assets will increase goodwill, which is calculated as a balancing figure and is not amortized on a systematic basis. It is difficult to ignore the fact that these two conflicting requirements serve the same conservative agenda that impairs the neutrality of financial reporting and seemingly contradicts the principles of the Conceptual Framework.

Intent-based accounting is in the yellow group

The less clear group that is more controversial in terms of its legitimacy, is the yellow group that lies between the two poles. Indeed, there may be a difference of opinion regarding its composition among different accounting experts. This group can include situations where the accounting model is based on the intention of management, as there is great sensitivity inherent in enforcing intent-based accounting. This can be illustrated in interpersonal terms by the phrase: “I loved you yesterday but today I no longer do… ” (and it would be difficult to argue with that…). This gives rise to a need to limit the ability to maneuver through anti-abuse provisions. Such a case exists for example in IAS 40, whose basic accounting model relies on the definition of investment property, which is essentially an intent-based definition. IAS 40’s anti-abuse provisions relate to restrictions on transfers after the initial classification to (or from) investment property, mainly from (or to) inventory and PPE. The purpose is, of course, to prevent abuse by arguing that management’s intention has changed, but one must understand that the price is creation of potential distortions due to late transfers to (or from) investment property, and the use of an inappropriate measurement basis, according to the standard’s rationale, until that date.

Another controversial case in the yellow group, that can be attributed to the IASB’s concern regarding the difficulty in enforcing management’s intentions, relates to the restrictions in IAS 36 on determining value in use. According to these restrictions, management’s intentions to make future asset improvements or restructuring are not taken into account when calculating value in use. Instead, future cash flows shall be estimated for the asset in its current condition.

From the Basis for Conclusions to IFRSs it can be learned that the cost-benefit issue regarding the use of anti-abuse provisions is an important consideration facing the Board. For example, there are cases where the IASB has decided not to sacrifice the neutrality of an accounting treatment in order to prevent an improper accounting abuse. An example would be the period for estimating expected credit losses. To prevent earnings management where expenses are recognized based on the timing that suits the entity’s management, while creating an earnings stockpile that will be released at the wish of management, the Board considered making it more difficult to revert back from a lifetime estimate to a 12-month estimate, compared to the conditions for the original transition from 12 months to lifetime. However, it was ultimately determined that the conditions for switching from 12-month to lifetime and back are symmetrical, with the understanding that anti-abuse considerations cannot override the neutrality of financial reporting. Of course, this determination should be applied consistently across all IFRSs.

The proposed amendment to IAS 32 should be updated

In summary, standard setters should reconsider the anti-abuse provisions found in the yellow group, but before doing so they need to revise, as soon as possible, the anti-abuse provisions included in the red group. It is unacceptable for accounting standards to sacrifice, in practice, proper accounting treatment due to concerns about manipulations. Let there be no doubt, when such distortions exist, they cause entities to always seek to circumvent them. For example, in the case of equity-based derivatives, entities will not enter into contracts that include settlement alternatives at the discretion of the issuer, where one of the alternatives is a liability. In addition, in the case of amortization of intangible assets, entities will simply “estimate” that they will use the intangible asset until the end of its useful life. That is, these provisions have no significant value, except that they lead to avoiding transactions and manipulative maneuvering. As a first step, the recently proposed amendment to IAS 32, which is currently open for public comment, should address the problematic provision mentioned above regarding share-based derivatives.

Mapping of the major anti-abuse provisions in IFRS into the three groups. What is your opinion?

(*) Written by Shlomi Shuv